- Published2 days ago

Share

Related Topics

Russia has cut the amount of the gas it sends to Europe by shutting the key Nord Stream 1 pipeline for the second time this summer.

It said the latest restrictions would last for three days, and were necessary to allow repairs.

Russia has already significantly reduced its energy exports to the continent, sending prices soaring, but denies using gas as a political weapon.

What is Nord Stream 1 and how much gas does it supply?

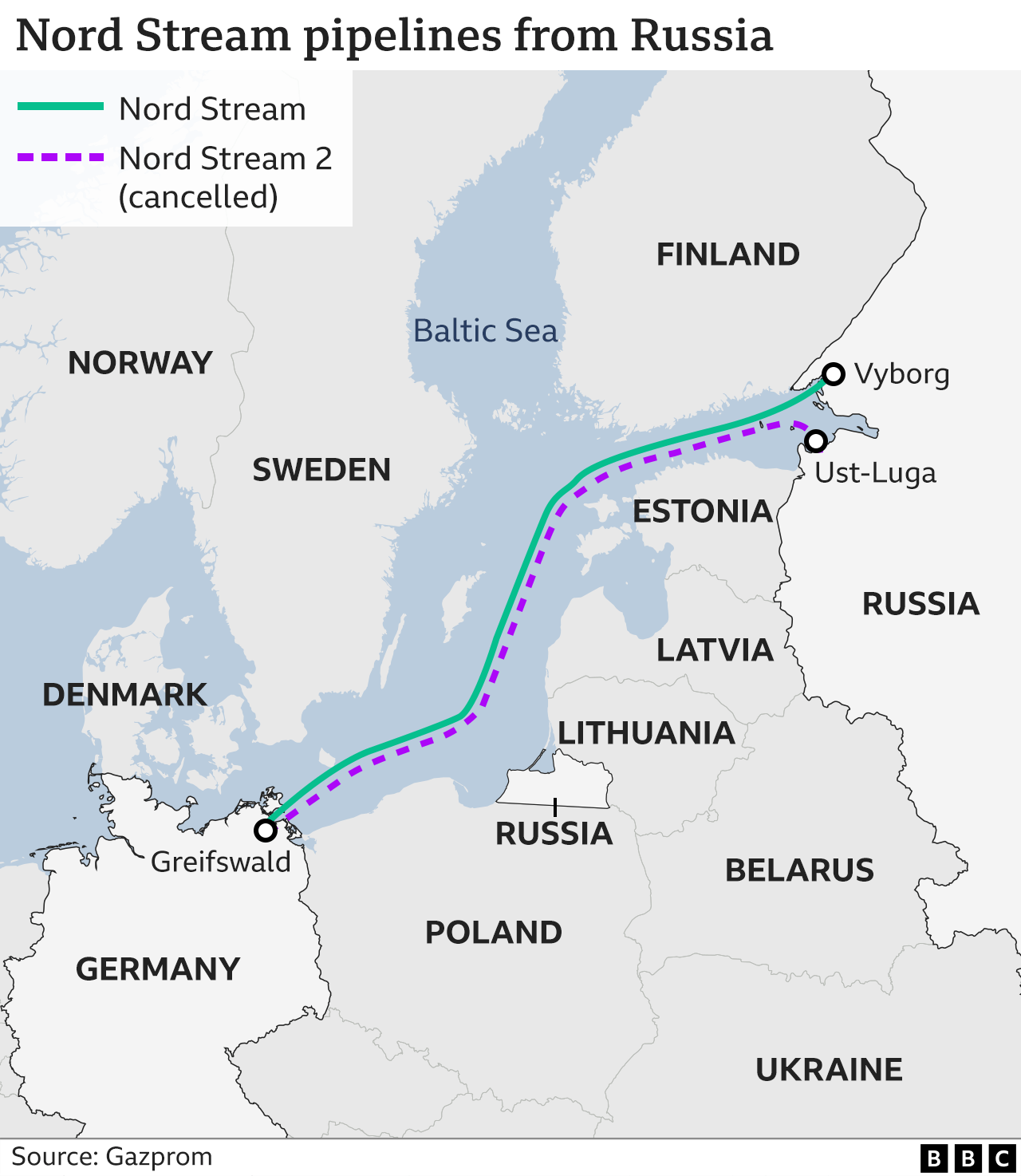

The Nord Stream 1 pipeline stretches 1,200km (745 miles) under the Baltic Sea from the Russian coast near St Petersburg to north-eastern Germany.

It opened in 2011, and can send a maximum of 170m cubic metres of gas per day from Russia to Germany.

It is owned and operated by Nord Stream AG, whose majority shareholder is the Russian state-owned company Gazprom.

Germany had also previously approved the construction of a parallel pipeline – Nord Stream 2 – but the project was halted after Russia invaded Ukraine.

How has Russia cut supplies?

In May, Gazprom closed the Yamal gas pipeline, which runs through Belarus and Poland and delivers gas to Germany and other European nations.

In June, Gazprom cut gas deliveries through Nord Stream 1 by 75% – from 170m cubic metres of gas a day to roughly 40m cubic metres.

Then, in July, it shut down Nord Stream 1 for 10 days, citing the need for maintenance.

Shortly after reopening, Gazprom halved the amount supplied to 20m cubic metres because of what it called faulty equipment.

Now it has completely halted all gas supplies to Europe through the pipeline, again claiming repairs were needed.

In August, Germany’s Economy Minister Robert Habeck denied there were any technical issues and said the pipeline was fully operational.

But Russian President Vladimir Putin’s spokesman insisted that Western sanctions have caused the interruptions by damaging Russian infrastructure.

Gazprom also said it would suspend gas deliveries to the French energy company Engie.

How is it hurting Europe?

Europe – and in particular Germany – has historically been very reliant on Russian gas to meet its energy needs.

When Russia announced its intention to restrict supply in July, within a day it had pushed up the wholesale price of gas in Europe by 10%.

Gas prices are now approximately 450% higher than they were this time last year.

“The market is so tight at the moment that any disruption in supply causes more hikes in the price of gas,” says Carole Nakhle, CEO of analysts Crystol Energy.

“This could cause slowdowns in European economies and accelerate the route towards recession.”

How is Europe reacting to the supply cuts?

Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky accused Russia of waging “an overt gas war against a united Europe”.

“Russia is weaponising gas more and more,” agrees Kate Dourian, fellow at the Energy Institute.

“It is trying to show that it is still an energy superpower, and can retaliate [against] the sanctions Europe has put on it.”

Before Russia invaded Ukraine, Germany got 55% of its gas from Russia. It has managed to reduce this to 35% and vowed to end imports completely.

As part of this, it has tried to get alternative supplies of gas from Norway and the Netherlands.

It is also buying five floating terminals to import liquefied natural gas from Qatar and the US, says Ms Dourian.

However, this will involve building new pipelines from the coast to the rest of Germany, which will take several months.

“You cannot build up a dependence on Russian gas as Germany has done, and change your sources of supply quickly,” says Ms Nakhle.

Germany is also increasing its use of coal and extending the life of power stations which it had been planning to shut down – despite the negative environmental impact.

Italy and Spain are trying to import more gas from Algeria.

“It’s every man for himself,” says Ms Dourian. “Everyone is taking their own steps to solve the energy shortage, and making their own deals.”

EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has promised to take further action, telling a conference in Slovenia that the energy market is “no longer fit for purpose”.

How is Europe reducing demand for gas?

The EU has worked out a deal in which member states cut usage by 15%.

The German government hopes to reduce gas usage by 2% by limiting the use of lighting and heating in public buildings this winter.

Spain has already brought in similar rules and Switzerland is considering doing the same.

Many European citizens are also taking steps themselves.

“In Germany,” says Ms Nakhle, “people are buying wood stoves and installing solar panels. Everyone is taking actions to reduce their use of gas.

“We should not underestimate how seriously people are taking the prospect of gas shortages.”